In Conversation with … François Matarasso

Artist, producer, researcher, writer and trainer

Community arts’ empowerment comes from encouraging people to use art to explore who they are and their relationship with the world in ways that can be shared with others.

“It allows us to write the world,” said François Matarasso, who will present twice at the 9th International Arts and Health Conference from 30 October – 1 November, including giving the Mike White Memorial Lecture.

“Art allows us to make sense of our experience and connect with others who share the sense we make,” he said.

“Without that capacity, we are only subject to other people’s sense-making. We are written by others. We lose agency.”

François has worked in community arts since 1981 as an artist, producer, researcher, writer and trainer, with experience across 40 countries, and has published influential work on the social outcomes of participation in the arts, and on the history, theory and practice of community art.

François was a close friend of Mike White, a pioneer in community arts and health who was behind establishment of the Centre for Medical Humanities at Durham University, and wrote the seminal book on the topic – Arts Development in Community Health: A Social Tonic. He died of cancer in June 2015.

“So often the difference we make is in what we do, not what we say,” François said.

“Mike’s work, as a producer, community arts worker, local authority officer, researcher, teacher and speaker touched thousands of people very deeply but always, I think, because he breathed his values.

“He was a gentle man, unduly modest, but brimful of enthusiasm and joy at the good things others achieved. I think, above all, he gave many people the confidence to fulfil their potential. That’s a great legacy.”

François’ memorial lecture is A Restless Art: Community Art and Empowerment, discussing community and participatory arts in Britain from a rights-based perspective.

He explained that community art had emerged in the 1960s as part of that decade’s “cultural revolution”, and ended as a movement in the late 1980s, since which time it has broadened and diversified under the name participatory arts.

“For me community art is a rights-based approach to co-operative artistic creation between professional and non-professional artists who set their goals and terms of success together … it is equally open to all ages, abilities, cultures, faiths etc,” François said.

Many would perhaps not know that participation in the arts is actually a right set out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (article 27), which states: “Everyone has the right to participate in the cultural life of the community and to enjoy the arts”.

François said there had been any number of stand-out successes over his years in community arts. In fact he says he has seen “very few genuinely bad community art projects, perhaps because even if they didn’t have the skills or knowledge, the people involved had a commitment that allowed them to create something at least worthwhile”.

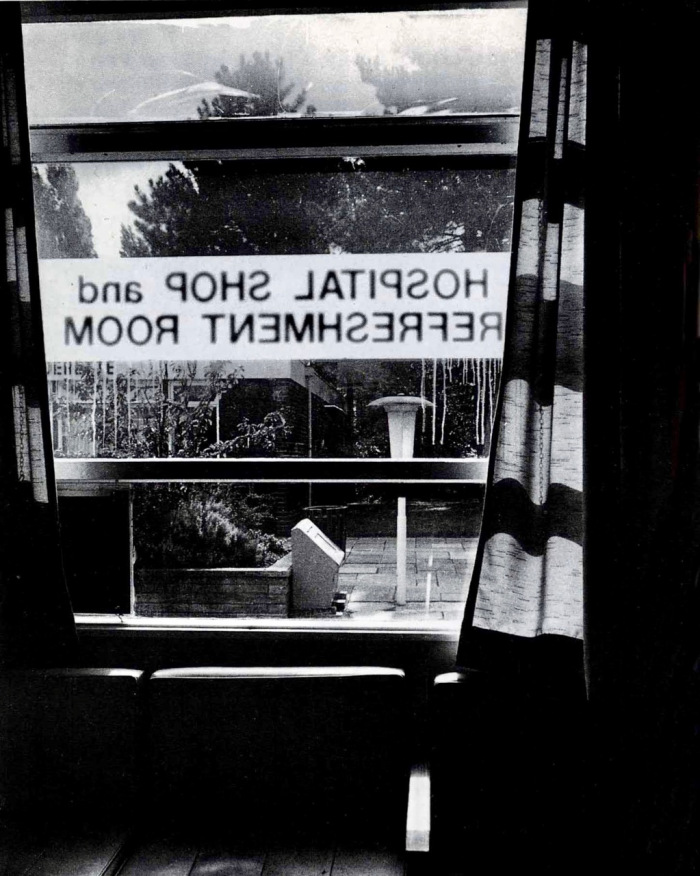

However, he pointed to one project in 1990 that remained particularly close to his heart – an 18-month residency by writer Rosie Cullen and photographer Ross Boyd which helped residents of a psychiatric hospital, which many had called home for years, deal with its closure and their move to small community-based facilities and homes.

François was working at the time with East Midlands Shape, a community art organisation involved with disabled people and people living in hospitals, care homes and prisons.

“It seemed important to do something on this policy that affected the lives of so many of the people we worked with,” François said.

“The result was a project called ‘Looking Back, Looking Forward’, in which residents of one hospital scheduled for closure could use art (photography, poems and stories) to reflect on their changing lives.”

The texts and images were collected into two books, one about life in the hospital and one about life outside, and a photographic exhibition toured the UK, including the Department of Health’s London headquarters.

“It was a symbolic way of ensuring that the voices of the people affected by the ‘Care in the Community’ (Thatcher Government policy which had forced the closures) would be heard where the decisions that transformed their lives were made,” François said.

“For me, it had everything that a good community arts project should be, in the sense of producing some great art that gave people who are undergoing life-changing events, not of their choosing, the power to express their feelings about the experience to each other but also to the wider public and even in the policy context.

“Nearly 30 years later, the words and images of that community art project still move me. Some have an aesthetic quality equal to that achieved by professional writers and photographers. Even the least accomplished – and there aren’t many – have truth and authenticity.”

And that, according to François, is the beauty of the arts and its potential for all, given access to its multi-faceted powers of expression, healing, wellbeing and empowerment.

“Because it comes from within, it is possible to create something extraordinary the first time you try,” he said.

“In fact sometimes not knowing the rules gives you more freedom than someone with decades of skill, experience and knowledge.

“That doesn’t mean that skill, experience and knowledge won’t increase your chance of making something great, but great things can happen without them, differently.”

- François Matarasso is giving the plenary Mike White Memorial Lecture, A Restless Art: Community Art and Empowerment and a second presentation on Artistry in Old Age at the 9th Annual International Arts and Health Conference – The Art of Good Health and Wellbeing – from 30 October to 1 November at the Art Gallery of NSW.

- François Matarasso’s visit to Australia has been sponsored by the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. François is giving a presentation at the NGA on Saturday 4 November. artsandhealth.org #artshealth17

– Alison Houston, writedirection gc